However, in most cases financial institutions require a waiting period of one to two years after the loan’s origination date, proof through an approved appraiser that the loan-to-value ratio is less than 80 percent, on-time payments during the waiting period, and a letter from the borrower requesting that the PMI be removed from the loanMortgage Characteristics A s mentioned above, mortgages are unique as capital market instruments because the characteristics (such as size, fees, and interest rate) of each mortgage held by a financial institution can differ. A mortgage contract between a financial institution and a borrower must specify all of the characteristics of the mortgage agreement. When a financial institution receives a mortgage application, it must determine whether the applicant qualifies for aloan.

Because most financial institutions sell or securitize their mortgage loans in the secondary mortgage market (discussed below), the guidelines set by the secondary market buyer for acceptability, as well as the guidelines set by the financial institution, are used to determine whether or not a mortgage borrower is qualified. Further, the characteristics of loans to be securitized will generally be more standardized than those that are not to be securitized. When mortgages are not securitized, the financial institution can be more flexible with the acceptance/rejection guidelines it uses and mortgage characteristics will be more varied

Collateral. As mentioned in the introduction, all mortgage loans are backed by a specific piece of property that serves as collateral to the mortgage loan. As part of the mortgage agreement, the financial institution will place a lien against a property that remains in place until the loan is fully paid off. A lien is a public record attached to the title of the property that gives the financial institution the right to sell the property if the mortgage borrower defaults or falls into arrears on his or her payments. The mortgage is secured by the lien that is, until the loan is paid off, no one can buy the property and obtain clear title to it. If someone tries to purchase the property, the financial institution can file notice of the lien at the public recorder’s office to stop the transaction.

Down Payment. As part of any mortgage agreement, a financial institution requires the mortgage borrower to pay a portion of the purchase price of the property (a down payment ) at the closing (the day the mortgage is issued). The balance of the purchase price is the face value of the mortgage (or the loan proceeds). A down payment decreases the probability that the borrower will default on the mortgage. A mortgage borrower who makes a large down payment invests more personal wealth into the home and, therefore, is less likely to walk away from the house should property values fall, leaving the mortgage unpaid. The drop in real estate values during the recent financial crisis caused many mortgage borrowers to walk away from their homes and mortgages, as well as many mortgage lenders to fail.

The size of the down payment depends on the financial situation of the borrower. Generally, a 20 percent down payment is required (i.e., the loan-to-value ratio may be no more than 80 percent). Borrowers that put up less than 20 percent are required to purchase private mortgage insurance (PMI). (Technically, the insurance is purchased by the lender (the financial institution) but paid for by the borrower, generally as part of the monthly payment.) In the event of default, the PMI issuer (such as PMI Mortgage Insurance Company) guarantees to pay the financial institution a portion (generally between 12 percent and 35 percent) of the difference between the value of the property and the balance remaining on the mortgage. As payments are made on the mortgage, or if the value of the property increases, a mortgage borrower can eventually request that the PMI requirement be removed. Every financial institution differs in its requirements for removing the PMI payment from a mortgage. However, in most cases financial institutions require a waiting period of one to two years after the loan’s origination date, proof through an approved appraiser that the loan-to-value ratio is less than 80 percent, on-time payments during the waiting period, and a letter from the borrower requesting that the PMI be removed from the loan.

Insured versus Conventional Mortgages. Mortgages are classified as either federally insured or conventional. Federally insured mortgages are originated by financial institutions, but repayment is guaranteed (for a fee of 0.5 percent of the loan amount) by either the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or the Veterans Administration (VA). In order to qualify, FHA and VA mortgage loan applicants must meet specific requirements set by these government agencies (e.g., VA-insured loans are available only to individuals who served and were honorably discharged from military service in the United States). Further, the maximum size of the mortgage is limited (the limit varies by state and is based on the cost of housing). For example, in 2010, FHA loan limits on single-family homes ranged from $271,050 to $729,750, depending on location and cost of living. FHA or VA mortgages require either a very low or zero down payment. (FHA mortgages require as little as a 3 percent down payment.)

Collateral. As mentioned in the introduction, all mortgage loans are backed by a specific piece of property that serves as collateral to the mortgage loan. As part of the mortgage agreement, the financial institution will place a lien against a property that remains in place until the loan is fully paid off. A lien is a public record attached to the title of the property that gives the financial institution the right to sell the property if the mortgage borrower defaults or falls into arrears on his or her payments. The mortgage is secured by the lien that is, until the loan is paid off, no one can buy the property and obtain clear title to it. If someone tries to purchase the property, the financial institution can file notice of the lien at the public recorder’s office to stop the transaction.

Down Payment. As part of any mortgage agreement, a financial institution requires the mortgage borrower to pay a portion of the purchase price of the property (a down payment ) at the closing (the day the mortgage is issued). The balance of the purchase price is the face value of the mortgage (or the loan proceeds). A down payment decreases the probability that the borrower will default on the mortgage. A mortgage borrower who makes a large down payment invests more personal wealth into the home and, therefore, is less likely to walk away from the house should property values fall, leaving the mortgage unpaid. The drop in real estate values during the recent financial crisis caused many mortgage borrowers to walk away from their homes and mortgages, as well as many mortgage lenders to fail.

The size of the down payment depends on the financial situation of the borrower. Generally, a 20 percent down payment is required (i.e., the loan-to-value ratio may be no more than 80 percent). Borrowers that put up less than 20 percent are required to purchase private mortgage insurance (PMI). (Technically, the insurance is purchased by the lender (the financial institution) but paid for by the borrower, generally as part of the monthly payment.) In the event of default, the PMI issuer (such as PMI Mortgage Insurance Company) guarantees to pay the financial institution a portion (generally between 12 percent and 35 percent) of the difference between the value of the property and the balance remaining on the mortgage. As payments are made on the mortgage, or if the value of the property increases, a mortgage borrower can eventually request that the PMI requirement be removed. Every financial institution differs in its requirements for removing the PMI payment from a mortgage. However, in most cases financial institutions require a waiting period of one to two years after the loan’s origination date, proof through an approved appraiser that the loan-to-value ratio is less than 80 percent, on-time payments during the waiting period, and a letter from the borrower requesting that the PMI be removed from the loan.

Insured versus Conventional Mortgages. Mortgages are classified as either federally insured or conventional. Federally insured mortgages are originated by financial institutions, but repayment is guaranteed (for a fee of 0.5 percent of the loan amount) by either the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or the Veterans Administration (VA). In order to qualify, FHA and VA mortgage loan applicants must meet specific requirements set by these government agencies (e.g., VA-insured loans are available only to individuals who served and were honorably discharged from military service in the United States). Further, the maximum size of the mortgage is limited (the limit varies by state and is based on the cost of housing). For example, in 2010, FHA loan limits on single-family homes ranged from $271,050 to $729,750, depending on location and cost of living. FHA or VA mortgages require either a very low or zero down payment. (FHA mortgages require as little as a 3 percent down payment.)

Conventional mortgages are mortgages held by financial institutions and are not federally insured (but as already discussed, they generally are required to be privately insured if the borrower’s down payment is less than 20 percent of the property’s value). Secondary market mortgage buyers will not generally purchase conventional mortgages that are not privately insured and that have a loan-to-value ratio of greater than 80 percent

Mortgage Maturities. A mortgage generally has an original maturity of either 15 or 30 years. Until recently, the 30-year mortgage was the one most frequently used. However, the 15-year mortgage has grown in popularity. Mortgage borrowers are attracted to the 15-year mortgage because of the potential saving in total interest paid (see below). However, because the mortgage is paid off in half the time, monthly mortgage payments are higher on a 15-year than on a 30-year mortgage. Financial institutions find the 15-year mortgage attractive because of the lower degree of interest rate risk on a 15-year relative to a 30-year mortgage. To attract mortgage borrowers to the 15-year maturity mortgage, financial institutions generally charge a lower interest rate on a 15-year mortgage than a 30-year mortgage. Most mortgages allow the borrower to prepay all or part of the mortgage principal early without penalty. In general, the monthly payment is set at a fixed level to repay interest and principal on the mortgage by the maturity date (i.e., the mortgage is fully amortized ). We illustrate this payment pattern for a 15-year fixed-rate mortgage in Figure 7–2 . However, other mortgages have variable interest rates and thus payments that vary (see below).

Mortgage Maturities. A mortgage generally has an original maturity of either 15 or 30 years. Until recently, the 30-year mortgage was the one most frequently used. However, the 15-year mortgage has grown in popularity. Mortgage borrowers are attracted to the 15-year mortgage because of the potential saving in total interest paid (see below). However, because the mortgage is paid off in half the time, monthly mortgage payments are higher on a 15-year than on a 30-year mortgage. Financial institutions find the 15-year mortgage attractive because of the lower degree of interest rate risk on a 15-year relative to a 30-year mortgage. To attract mortgage borrowers to the 15-year maturity mortgage, financial institutions generally charge a lower interest rate on a 15-year mortgage than a 30-year mortgage. Most mortgages allow the borrower to prepay all or part of the mortgage principal early without penalty. In general, the monthly payment is set at a fixed level to repay interest and principal on the mortgage by the maturity date (i.e., the mortgage is fully amortized ). We illustrate this payment pattern for a 15-year fixed-rate mortgage in Figure 7–2 . However, other mortgages have variable interest rates and thus payments that vary (see below).

In addition to 15- and 30-year fixed-rate and variable-rate mortgages, financial institutions sometimes offer balloon payment mortgages . A balloon payment mortgage requires a fixed monthly interest payment (and, sometimes, principal payments) for a three- to five-year period. Full payment of the mortgage principal (the balloon payment) is then required at the end of the period, as illustrated for a five-year balloon payment mortgage in Figure 7–2 . Because they normally consist of interest only, the monthly payments prior to maturity are lower than those on an amortized loan (i.e., a loan that requires periodic repayments of principal and interest). Generally, because few borrowers save enough funds to pay off the mortgage in three to five years, the mortgage principal is refinanced at the current mortgage interest rate at the end of the balloon loan period (refinancing at maturity is not, however, guaranteed). Thus, with a balloon mortgage the financial institution essentially provides a long-term mortgage in which it can periodically revise the mortgage’s characteristics

Interest Rates. Possibly the most important characteristic identified in a mortgage contract is the interest rate on the mortgage. Mortgage borrowers often decide how much to borrow and from whom solely by looking at the quoted mortgage rates of several financial institutions. In turn, financial institutions base their quoted mortgage rates on several factors. First, they use the market rate at which they obtain funds (e.g., the fed funds rate or the rate on certificates of deposit). The market rate on available funds is the base rate used to determine mortgage rates. Figure 7–3 illustrates the trend in 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury bond rates from 1980 through 2010. Note the declining trend in mortgage (and T-bond) rates over the period. During the first week of July 2010, the average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage dropped to an all time low of 4.58 percent, down from 4.69 percent the previous week, also an all-time record low. One year earlier, the average rate was 5.32 percent. Once the base mortgage rate is determined, the rate on a specific mortgage is then adjusted for other factors (e.g., whether the mortgage specifies a fixed or variable (adjustable) rate of interest and whether the loan specifies discount points and other fees), as discussed below.

Interest Rates. Possibly the most important characteristic identified in a mortgage contract is the interest rate on the mortgage. Mortgage borrowers often decide how much to borrow and from whom solely by looking at the quoted mortgage rates of several financial institutions. In turn, financial institutions base their quoted mortgage rates on several factors. First, they use the market rate at which they obtain funds (e.g., the fed funds rate or the rate on certificates of deposit). The market rate on available funds is the base rate used to determine mortgage rates. Figure 7–3 illustrates the trend in 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury bond rates from 1980 through 2010. Note the declining trend in mortgage (and T-bond) rates over the period. During the first week of July 2010, the average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage dropped to an all time low of 4.58 percent, down from 4.69 percent the previous week, also an all-time record low. One year earlier, the average rate was 5.32 percent. Once the base mortgage rate is determined, the rate on a specific mortgage is then adjusted for other factors (e.g., whether the mortgage specifies a fixed or variable (adjustable) rate of interest and whether the loan specifies discount points and other fees), as discussed below.

Fixed versus Adjustable-Rate Mortgages. Mortgage contracts specify whether a fixed or variable rate of interest will be paid by the borrower. A fixed-rate mortgage locks in the borrower’s interest rate and thus required monthly payments over the life of the mortgage, regardless of how market rates change. In contrast, the interest rate on an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) is tied to some market interest rate or interest rate index. Thus, the required monthly payments can change over the life of the mortgage. ARMs generally limit the change in the interest rate allowed each year and during the life of the mortgage (called caps ). For example, an ARM might adjust the interest rate based on the average Treasury bill rate plus 1.5 percent, with caps of 1.5 percent per year and 4 percent over the life of the mortgage.

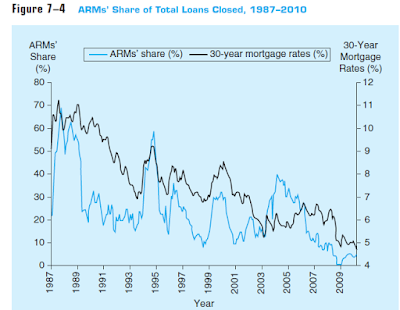

of the mortgage. Figure 7–4 shows the percentage of ARMs relative to all mortgages closed and 30-year mortgage rates from 1987 through 2010. Notice that mortgage borrowers generally prefer fixed-rate loans to ARMs when interest rates in the economy are low. If interest rates rise, ARMs may cause borrowers to be unable to meet the promised payments on the mortgage. In contrast, most mortgage lenders prefer ARMs when interest rates are low. When interest rates eventually rise, ARM payments on their mortgage assets will rise. Since deposit rates and other liability rates too will be rising, it will be easier for financial institutions to pay the higher interest rates to their depositors when they issue ARMs. However, higher interest payments mean mortgage borrowers may have trouble making their payments. Thus, default risk increases. Such was the case during the recent financial crisis. As the general level of interest rates in the economy rose, rates on ARMs increased to the point that many borrowers had trouble meeting their payments. The result (as discussed above) was a record number of foreclosures. Thus, while ARMs reduce a financial institution’s interest rate risk, they also increase its default risk. Note from Figure 7–4 the behavior of the share of ARMs to fixed-rate mortgages over the period 1996 through 1999 when interest rates fell. Notice that borrowers’ preferences

for fixed-rate mortgages prevailed over this period, as a consistently low percentage of total mortgages closed were ARMs (over this period the percentage of ARMs to total mortgages issued averaged only 14 percent). During the height of the financial crisis (late 2008–early 2009), as interest rates were dropping to historic lows, virtually no ARMs were issued.

Discount Points. Discount points (or more often just called points) are fees or payments made when a mortgage loan is issued (at closing). One discount point paid up front is equal to 1 percent of the principal value of the mortgage. For example, if the borrower pays 2 points up front on a $100,000 mortgage, he or she must pay $2,000 at the closing of the mortgage. While the mortgage principal is $100,000, the borrower effectively has received $98,000. In exchange for points paid up front, the financial institution reduces the interest rate used to determine the monthly payments on the mortgage. The borrower determines whether the reduced interest payments over the life of the loan outweigh the up-front fee through points. This decision depends on the period of time the borrower expects to hold the mortgage (see below).

Discount Points. Discount points (or more often just called points) are fees or payments made when a mortgage loan is issued (at closing). One discount point paid up front is equal to 1 percent of the principal value of the mortgage. For example, if the borrower pays 2 points up front on a $100,000 mortgage, he or she must pay $2,000 at the closing of the mortgage. While the mortgage principal is $100,000, the borrower effectively has received $98,000. In exchange for points paid up front, the financial institution reduces the interest rate used to determine the monthly payments on the mortgage. The borrower determines whether the reduced interest payments over the life of the loan outweigh the up-front fee through points. This decision depends on the period of time the borrower expects to hold the mortgage (see below).

- Other Fees. In addition to interest, mortgage contracts generally require the borrower to pay an assortment of fees to cover the mortgage issuer’s costs of processing the mortgage. These include such items as:

- Application fee. Covers the issuer’s initial costs of processing the mortgage application and obtaining a credit report.

- Title search. Confirms the borrower’s legal ownership of the mortgaged property and ensures there are no outstanding claims against the property. Title insurance. Protects the lender against an error in the title search.

- Appraisal fee. Covers the cost of an independent appraisal of the value of the mortgaged property.

- Loan origination fee. Covers the remaining costs to the mortgage issuer for processing the mortgage application and completing the loan.

- Closing agent and review fees. Cover the costs of the closing agent who actually closes the mortgage.

- Other costs. Any other fees, such as VA loan guarantees, or FHA or private mortgage insurance.

Figure 7–5 presents a sample closing statement in which the various fees are reportedand the payment required by the borrower at closing is determined.

Mortgage Refinancing. Mortgage refinancing occurs when a mortgage borrower takes out a new mortgage and uses the proceeds obtained to pay off the current mortgage. Mortgage refinancing involves many of the same details and steps involved in applying for a new mortgage and can involve many of the same fees and expenses. Mortgages are most often refinanced when a current mortgage has an interest rate that is higher than the current interest rate. As coupon rates on new mortgages fall, the incentive for mortgage borrowers to pay off old, high coupon rate mortgages and refinance at lower rates increases. Figure 7–6 shows the percentage of mortgage originations that involved refinancings and 30-year mortgage rates from 1990 through 2010. Notice that as mortgage rates fall the percentage of mortgages that are refinancings increases. For example, as mortgage rates fell in the early and late 2000s, refinancings increased to over 70 percent of all mortgages originated. By refinancing the mortgage at a lower interest rate, the borrower pays less each montheven if the new mortgage is for the same amount as the current mortgage. Traditionally, the decision to refinance involves balancing the savings of a lower monthly payment against the costs (fees) of refinancing. That is, refinancing adds transaction and recontracting costs. Origination costs or points for new mortgages, along with the cost of appraisals and credit checks, frequently arise as well. An often-cited rule of thumb is that the interest rate for a new mortgage should be 2 percentage points below the rate on the current mortgage for refinancing to make financial sense.

No comments:

Post a Comment