Income Taxes

The discussion thus far has considered the measurement of assets, liabilities, revenues, gains, expenses, and losses before considering any income tax effects. Everyone is aware that taxes are a significant aspect of doing business, but few understand how taxes impact financial statements. The objective of this brief discussion is to familiarize you with the basic concepts underlying the treatment of income taxes in the financial statements. To fully understand business transactions and the impact they have on firms, you need to understand their income tax effects. Further, analyzing profitability requires that you understand tax effects on profitability. Thus, an overview of the required accounting for income taxes under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is necessary.

The discussion thus far has considered the measurement of assets, liabilities, revenues, gains, expenses, and losses before considering any income tax effects. Everyone is aware that taxes are a significant aspect of doing business, but few understand how taxes impact financial statements. The objective of this brief discussion is to familiarize you with the basic concepts underlying the treatment of income taxes in the financial statements. To fully understand business transactions and the impact they have on firms, you need to understand their income tax effects. Further, analyzing profitability requires that you understand tax effects on profitability. Thus, an overview of the required accounting for income taxes under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is necessary.

The fundamental reason for the difficulty in understanding the financial reporting of income taxes is that financial reporting of income uses one set of rules (U.S. GAAP, for example), while taxable income uses another set of rules (the Internal Revenue Code, for example). The differences between these sets of rules triggers differences in the timing and amount of tax expense on the income statement and the actual taxes payable to the government, which necessitates recognizing deferred income tax assets and liabilities. These differences are analogous to differences between financial reporting rules and cash basis accounting, which necessitate the use of various accruals such as accounts receivable and accounts payable. Thus, an understanding of financial statement analysis requires the appreciation that there are (at least) three primary methods by which financial performance can be measured, as shown in Exhibit 2.9.

income), cash flows (income taxes paid are an operating use of cash), and assets and liabilities (for accrued taxes payable and deferred tax assets or liabilities). Income tax expense under accrual accounting for a period does not necessarily equal income taxes owed under the tax laws for that period (for which the firm must pay cash). The discussion first helps you clarify nomenclature that differs between financial reporting of income taxes (in financial statements) and elements of income taxes for tax reporting (on tax returns). Exhibit 2.10 demonstrates the primary differences. Both financial reporting and tax reporting begin with revenues, but revenue recognition rules for financial reporting do not necessarily lead to the same figure for revenues as reported for tax reporting. Under tax reporting, firms report ‘‘deductions’’ rather than ‘‘expenses.’’ Revenues minus deductions equal ‘‘taxable income’’ (rather than ‘‘income before taxes,’’ or ‘‘pretax income’’). Finally, taxable income determines ‘‘taxes owed,’’ which can be substantially different from ‘‘tax expense’’ on the income statement, as highlighted later in this section. The balance sheet recognizes the difference between the two amounts as deferred tax assets or deferred tax liabilities. The balance sheet also recognizes any taxes owed at year-end (beyond the estimated tax payments firms may have made throughout the year) as a current liability for income taxes payable.

A simple example illustrates the issues in accounting for income taxes. Exhibit 2.11 sets forth information for the first two years of a firm’s operations. The first column for each year shows the financial reporting amounts (referred to as ‘‘book amounts’’). The second column shows the amounts reported to income tax authorities (referred to as ‘‘tax amounts’’ or ‘‘tax reporting’’). To clarify some of the differences between book and tax effects in the first two columns, the third column indicates the effect of each item on cash flows. Assume for this example and those throughout this chapter that the income tax rate is 40%. Additional information on each item is as follows:

does not tax interest on state and municipal bonds, so this amount is excluded from taxable income.

- Depreciation Expense: The firm purchases equipment for $120 cash, and the equipment has a two-year life. It depreciates the equipment using the straightline method for financial reporting, recognizing $60 of depreciation expense on its books each year. Income taxing authorities permit the firm to deduct $80 of depreciation of the asset in the first year, and only $40 of depreciation for tax reporting in the second year.

- Warranty Expense: The firm estimates that the cost of providing warranty services on products sold equals 2% of sales. It recognizes warranty expense of $10 (0.02 3 $500) each year for financial reporting, which links the estimated cost of warranties against the revenue from the sale of products subject to warranty. Income tax laws do not permit firms to claim a deduction for warranties in computing taxable income until they make cash expenditures to provide warranty services. Assume that the firm incurs cash costs of $4 in the first year and $12 in the second year.

- Other Expenses: The firm incurs and pays other expenses of $300 each year.

- Income before Taxes and Taxable Income: Based on the preceding assumptions, income before taxes for financial reporting is $155 each year. Taxable income is $116 in the first year and $148 in the second year.

- Taxes Payable: Assume for purposes here that the firm pays all income taxes at each year-end

Income before taxes for financial reporting differs from taxable income for the following principal reasons:

1. Permanent Differences: There are revenues and expenses that firms include in net income for financial reporting but that never appear on the income tax return. The amount of interest earned on the municipal bond is a permanent revenue difference. Examples of expenses that would be disallowed as deductions include executive compensation above a specified cap, certain entertainment expenses, political and lobbying expenses, and some fines and penalties.

2. Temporary Differences: There are revenues and expenses that firms include in both net income and taxable income but in different periods. These timing differences are ‘‘temporary’’ until they ‘‘reverse.’’ Straight-line versus accelerated depreciation expense is a temporary difference. The firm recognizes total depreciation of $120 over the life of the equipment for both financial and tax reporting but in a different pattern over time. Similarly, warranty expense is a temporary difference. The firm recognizes a total of $20 of warranty expense over the two-year period for financial reporting. It deducts only $16 over the two-year period for tax reporting. If the firm’s estimate of total warranty costs turns out to be correct, the firm will deduct the remaining $4 of warranty expense for tax reporting infuture years when it provides warranty service

A central conceptual question in accounting for income taxes concerns the measurement of income tax expense on the income statement for financial reporting.

A central conceptual question in accounting for income taxes concerns the measurement of income tax expense on the income statement for financial reporting.

- Should the firm compute income tax expense based on book income before taxes ($155 for each year in Exhibit 2.11)?

- Should the firm compute income tax expense based on book income before taxes but excluding permanent differences [$130 ($155 – $25) for each year in Exhibit 2.11]?

- Should the firm compute income tax expense based on taxable income ($116 in the first year and $148 in the second year in Exhibit 2.11)?

U.S. GAAP and IFRS require firms to follow the second approach, which complicates an understanding of income tax accounting because the amount upon which tax expense is based does not necessarily appear on the income statement (that is, income before taxes minus permanent differences). For this reason, U.S. GAAP and IFRS require disclosure within the income tax footnote to the financial statements that shows how the firm calculates income tax expense. This should clear up a misconception that income tax expense is the amount of income taxes currently owed (the third approach). If a firm does not have any permanent differences, there is no difference between the first and second approaches

The rationale behind basing income tax expense on income before taxes minus permanent differences is that it aligns the recognition of all tax consequences of items and events already recognized in the financial statements or on tax returns in the period they occur. Thus, tax expense is based on book income, which often diverges from what is shown on the tax returns. Permanent differences do not affect taxable income or income taxes paid in any year, and firms do not recognize income tax expense or income tax savings on permanent differences. Continuing the example above, under the second approach, income tax expense is$52 (0.4 3 $130) in each year. The impact on the financial statements of recognizing the tax expense, taxes paid, and associated deferred tax accounts is as follow

Income tax expense of 52.0 is recognized, which reduces net income, whereas the firm only pays cash taxes of 46.4. The deferred tax asset measures the future tax saving that the firm will realize when it provides warranty services in future years and claims a tax deduction for the realization of expenses that are estimated in the first year. The firm expects to incur $6 ($10 – $4) of warranty costs in the second year and later years. When it incurs these costs, it will reduce its taxable income, which will result in lower taxes owed for the year, all else equal. Hence, the deferred tax asset of $2.4 (0.4 3 $6) reflects the expected future tax savings from the future deductibility of amounts already expensed for financial reporting but not yet deducted for tax reporting. The $8 (0.4 3 $20) deferred tax liability measures taxes that the firm must pay in the second year when it recognizes $20 less depreciation for tax reporting than for financial reporting

The following summarizes the differences between book and tax amounts and the underlying cash flows. The $25 of interest on municipal bonds is a cash flow, but it is not reported on the tax return (it is a permanent difference). Depreciation is an expense that is a temporary difference between tax reporting and financial reporting but does not use cash. The firm recognized warranty expense of $10 in measuring net income but used only $4 of cash in satisfying warranty claims, which is the amount allowed to be deducted on the tax return. Finally, the firm recognized $52 of income tax expense in measuring net income but used only $46.4 cash for income taxes due to permanent and temporary differences. Overall, net income is $103, taxable income is $116, and net cash flows are $54.6. The discrepancy between net income and net cash flows is in large part due to the difference between cash invested in long-term assets relative to periodic depreciation. In the second year, the impact on the financial statements of the income tax effects is as follows:

The following summarizes the differences between book and tax amounts and the underlying cash flows. The $25 of interest on municipal bonds is a cash flow, but it is not reported on the tax return (it is a permanent difference). Depreciation is an expense that is a temporary difference between tax reporting and financial reporting but does not use cash. The firm recognized warranty expense of $10 in measuring net income but used only $4 of cash in satisfying warranty claims, which is the amount allowed to be deducted on the tax return. Finally, the firm recognized $52 of income tax expense in measuring net income but used only $46.4 cash for income taxes due to permanent and temporary differences. Overall, net income is $103, taxable income is $116, and net cash flows are $54.6. The discrepancy between net income and net cash flows is in large part due to the difference between cash invested in long-term assets relative to periodic depreciation. In the second year, the impact on the financial statements of the income tax effects is as follows:

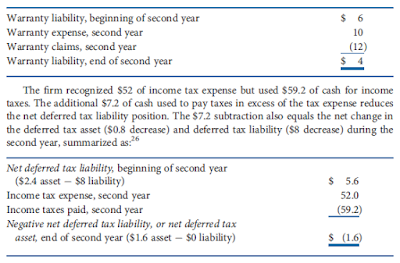

As in the first year, income tax is recognized as the effective tax rate times the pretax income, and cash paid for taxes equals the tax rate times taxable income. The temporary difference related to depreciation completely reverses in the second year, so the firm reduces the deferred tax liability to zero, which increases income taxes currently payable by $8. The temporary difference related to the warranty partially reversed during the second year, but the firm created additional temporary differences in that year by making another estimate of future warranty expense. For the two years as a whole, warranty expense for financial reporting of $20 ($10 þ $10) exceeds the amount recognized for tax reporting of $16 ($4 þ $12). Thus, the firm will recognize a deferred tax asset representing future tax savings of $1.6 (0.4 3 $4). The deferred tax asset had a balance of $2.4 at the end of the first year, so the adjustment in the second year reduces the balance of the deferred tax asset by $0.8 ($2.4 – $1.6).

Now consider the cash flow effects for the second year. Cash flow from operations is $153.8. Again, depreciation expense is a noncash expense of $60. The firm recognized warranty expense of $10 for financial reporting but used $12 of cash to satisfy warranty claims. The $2 subtraction also equals the net reduction in the warranty liability during the second year, as the following analysis shows:

Now consider the cash flow effects for the second year. Cash flow from operations is $153.8. Again, depreciation expense is a noncash expense of $60. The firm recognized warranty expense of $10 for financial reporting but used $12 of cash to satisfy warranty claims. The $2 subtraction also equals the net reduction in the warranty liability during the second year, as the following analysis shows:

At the end of the second year, the following totals for net income, cash flows, and tax amounts are as follows

The remaining net cash flows associated with the warranty will be the $4.0 cash outflow, offset by the $1.6 tax expense savings when those warranty payments are deductible. When the warranty liability is finally settled, net income will equal net cash flows. In addition, total net cash flows of $208.4 exceed the net of taxable income and taxes paid of $158.4, a difference of $50.0. This difference reflects the total of permanent differences across the two years ($25.0 þ $25.0). We reconciled net cash flows to net income above, so this additional $50.0 difference reflects a permanent difference between what is reported on the tax returns and what appears in the financial statements (both the income statement and statement of cash flows).

No comments:

Post a Comment